I have always thought that there was something curiously contemporary about the Water Garden at Studley Royal. It seems to have more in common with modern British landscapes than with Le Notre’s work at Versailles or Chantilly built just a few years earlier, or English Landscape Gardens of the mid-18th century.

Kim Wilkie’s Orphean Hades at Boughton House

Seeing earth moved purposefully around to create geometric shapes has always interested me, in the same way that I find labyrinths, or Stonehenge strangely satisfying and reassuring. In the last 20 years or so there has been a renewed interest in the sculptural possibilities of grass, earthworks and water in such British gardens as Charles Jenck’s Garden of Cosmic Speculation and the many projects of Kim Wilkie, such as The Orphean Hades created at Boughton House in Northamptonshire.

Charles Bridgeman’s Amphitheatre at Claremont

So why does Studley Royal seem modern? I think it is because historically there is virtually nothing to compare it with. It was a transitional style of garden that looked back to the formality of French gardens but forward to the freer more naturalistic designs of William Kent and Capability Brown; and as such in nearly every instance was swept away as garden fashion moved on. The now largely forgotten Charles Bridgeman was the leading exponent of this style, his amphitheatre at Claremont being a lasting testament.

Studley Royal – temple of Piety and Moon and Crescent Ponds

Temple of Piety and Neptune

Water gardens in the French style with their spectacular fountains grounded their chateaux in the predominantly flat landscape, and were over-viewed from the main first floor rooms. At Studley, the ‘Pleasure Garden’ was built as a separate entity away from the house, and the formal geometric ponds were designed to be seen as calm tranquil mirrors rather than turbulent fountain ponds. These were glimpsed as composed picturesque views from the High Ride on the steeply wooded slopes overlooking the valley.

View from the High Ride

I believe the clue to why Studley Royal didn’t follow fashion and turn its geometric ponds into serpentine lakes lies in the character of the garden’s creator, John Aislabie. As Chancellor of the Exchequer he had been the driving force behind the South Sea Company, a hugely speculative venture that ended with his disgrace, internment in the Tower of London for a year, and retirement from public life.

The Banqueting House

He seems to me to have had a personal passion for his water garden, and although he liked visitors to see it I sense there was no desire to be abreast of the latest fashion. For instance, he did not feel the need to rebuild his old manor house Studley Royal Hall in the newly popular Palladian style, but he was no country bumpkin. When he built his Banqueting House, and new stable block, he hired one of the most famous Palladian architects, Colen Campbell to carry out the work.

A Fishing Tabernacle

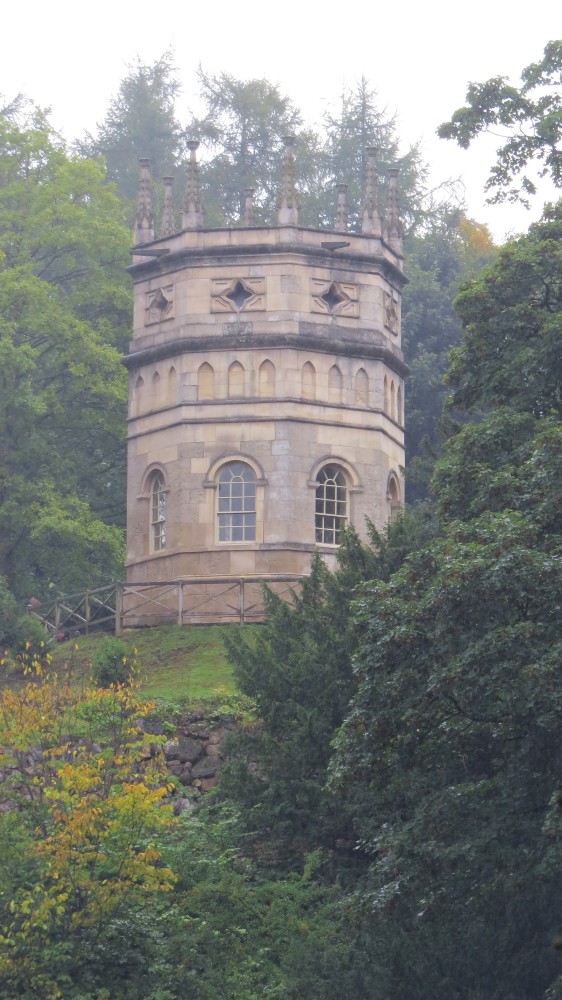

I think Aislabie knew he had created something of timeless and breath-taking beauty in a spectacular setting, and all he needed to do over the subsequent 22 years was to embellish and fine tune his garden with new features, such as the Fishing Tabernacles, and the Gothic Octagon Tower.

The Octagon Tower

Upon John Aislabie’s death in 1742, Studley Royal passed to his son William. The Aislabies had always coveted the neighbouring estate of Fountains Abbey, but it was not until 1767 that William was eventually able to purchase it, and incorporate it into the Studley Royal Water Garden.

Fountains Abbey

Garden style had moved on and there was a growing interest in romantic landscape. The Gothic gloom of Fountains Abbey, probably the most spectacular ruined abbey in the country, gave the garden a new visual point of reference. William set to work linking the two estates by creating meadows and changing the stony watercourse of the River Skel with weirs, into a broad sleepy river. I’m not sure if William felt the same way about the Water Garden as his father, but I suspect that this may have been the reason why it was not updated. William certainly had no such hesitation about remodelling his father’s medieval manor as a neo-Classical mansion.

The River Skel

Studley Royal and Fountains Abbey is one of England’s greatest and most unique landscapes, that thrills me on each visit, and although a historical garden, it has lessons for the future. I think it is a type of landscape whose time has come around again, and expect to see more gardens in the near future that harken back to its unusual style.

Where: Fountains Abbey and Studley Royal, Ripon, North Yorkshire HG4 3DY

Contact: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/fountains-abbey

| Setting | 5 | Interest for Children | 4 |

| Concept | 5 | Accessibility | 3 |

| Design Execution | 4 | Cafe | 5 |

| Hard Landscaping | 4 | ||

| Planting | 3 | ||

| Maintenance | 4 | ||

| Garden | 25/30 | Facilities | 12/15 |